Text: Thomas Masuch, 18 February 2024

Given the limited production quantities involved, you’d think the marine industry would be a prime sector for 3D printing. In recent years, however, the development of additive manufacturing in this area has not really progressed at a rapid pace. Now AM seems to have arrived on the water: Entire boats are being printed, and the leading nations have launched naval projects on how AM can be installed on ships.

As the German Navy’s 3D printing coordinator, Lieutenant Captain Dr. Sascha Hartig is responsible for implementing additive manufacturing within this branch of the military. In just seven months, Hartig and his team have found 153 use cases, most of which involve small plastic parts where 3D printing "helps improve the operational readiness of a ship," as he puts it. Usually, replacements for defective components are 3D-printed and remain in use until a ship arrives at the next supply port, where original spare parts are available. The German Navy has already received praise for this new technology from the highest level: "The introduction of 3D printing marks the beginning of a new era for the Navy in terms of improving spare parts availability and spontaneous response to emergency repairs," said Vice Admiral Jan Christian Kaack, the navy's inspector.

Montage of the 3D-printed WAAMpeller from Ramlab. Image: Ramlab

The German Navy has had printers on board for several years now. They were initially used for research, but are now serving more and more practical purposes, such as in producing valves for wastewater treatment or housings for electronic components that are no longer available from the manufacturer after 10 years. The printers also make seawater filters made of nylon – which, unlike steel components, do not corrode – and temporary components for the fire extinguishing system.

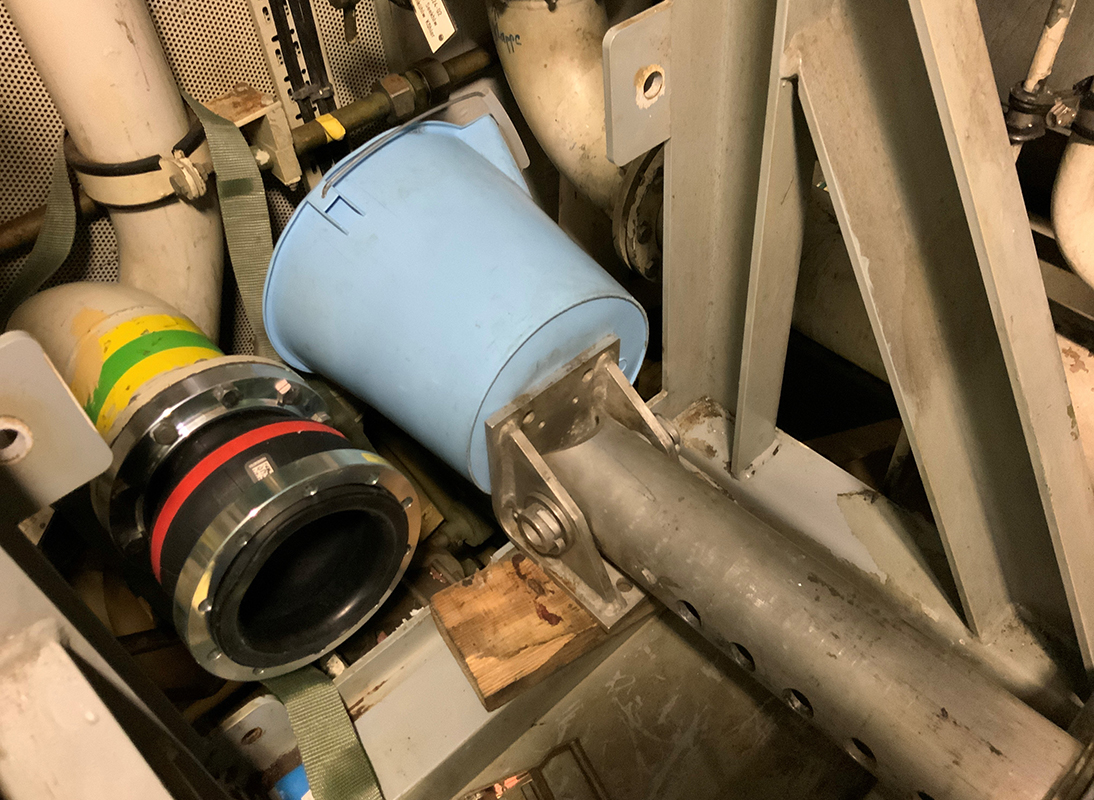

In another case, a blind flange for a dismantled heat exchanger in a ship’s seawater cooling system was printed at sea. This fixed a defective valve that had been allowing 180 liters of water to leak into the ship every day.

In addition to repair options like these, Hartig uses 3D printing to print prototypes, for example, and thereby leverages additive manufacturing as a driver of innovation for the military. "This sometimes brings a gleam to the soldiers' eyes,” he reveals. In the future, Hartig wants to significantly expand the German Navy’s use of AM. One key here is networking and the international development of standards. Among other benefits, ships will then be able to supply each other with temporary components from their 3D printers during international maneuvers, meaning not every ship will need to have a full range of AM parts on board.

Lieutenant Captain Sascha Hartig was also on the Formnext 2023 conference schedule to talk about the additive developments in the German Navy. Image: Mathias Kutt

3D printing was tested on the frigate Sachsen. Image. German Navy

One of the machines installed was a 3D printer from Stratasys. Image: German Navy

Due to a defective valve, 180 liters of water leaked into the ship every day. Picture: German Navy

The leak could be stopped by using 3D printing. Image: German Navy

The leak could be stopped by using 3D printing. Image: German Navy

Propellers and underwater habitats

Based in the port of Rotterdam, Ramlab is one of the companies with the most AM experience in the marine sector. The company focuses on wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) and 3D-printed the WAAMpeller back in 2017 – "our best-known shipbuilding part", as CEO Vincent Wegener describes it. The world's first 3D-printed and certified propeller, which weighs 220 kilograms and has a diameter of 150 centimeters, was created in collaboration with Damen Shipyards, Promarin, Autodesk, and Bureau Veritas. Since then, Ramlab has worked with the Royal Netherlands Navy and DNV on printing a stainless-steel impeller and was involved in 3D-printing the first high-pressure components for Vallourec in the oil and gas industry. Its current project, meanwhile, is underwater: Six robotic MaxQ systems arranged in a hexagonal configuration are being used to create the world's first 3D-printed underwater habitats for humans. The robots synchronously produce the hull segments, which weigh more than 30 tons and are subsequently certified by DNV.

Applications on the rise around the world

Additive manufacturing can now also be found on more and more naval vessels worldwide. The Indian Navy, for example, has printed a centrifugal pump impeller together with the 3D printing service provider think3D, and the Australian Navy has purchased a WarpSpeed3D metal printer to improve the maintenance of patrol vessels. 3D printers are also in use on US Navy ships: The USS New Hampshire, for instance, has had a Markforged X7 Field Edition on board since July 2022, which it has used for things like fixing leaking pipes and printing electronic housings. The 257-meter-long USS Bataan has also employed a Phillips Additive Hybrid to 3D-print and post-process a nozzle for a saltwater outlet valve.

Additive manufacturing is also playing an increasingly important role in shipbuilding itself, even if many projects are still in the development stage. For example, the US Navy is working with the Australian AM company AML3D on the construction of submarines, which involves manufacturing a prototype of a component weighing several tons using the WAAM process.

In the naval sector, Ramlab CEO Wegener sees the greatest potential for WAAM in the combination of high-quality parts and a significant reduction in lead times. “This is why you see the US Navy actively pursuing this technology for their submarines, for instance,” he points out.

Production of the WAAMpeller...

....and event after installation on the ship. Images: Ramlab

Certification remains a challenge

According to Lieutenant Captain Hartig, the fact that additive manufacturing is not more widespread in naval applications is due to this being a rather conservative area of mechanical engineering. “Also, components in the metal sector are usually very large, and the development of the necessary machines has only taken place in recent years. The alloys used in shipbuilding are not, or at least have not been, the focus of the AM industry,” he explains. In addition, a major problem in this field is often that design data is the property of shipyards, and therefore not available. As a further hurdle, Hartig mentions the necessary personnel expertise, including in design, printer operation, and post-processing. “This is very difficult to achieve with the resources available.” Nevertheless, Hartig's experiments with the German Navy have been successful “because we brought additional resources on board in the form of personnel and materials and thus did not restrict the crew.”

Meanwhile, Vincent Wegener believes that the biggest challenge in the further development of 3D printing in the marine sector is the process of certifying printed parts. “Not only companies starting with WAAM need to go through a learning process to print parts and certify them; certifying bodies had and still have to go through this process, as well.” According to Wegener, knowledge of the process and acceptance of WAAM as an alternative manufacturing technology is steadily increasing. “After all, necessity tends to steer developments towards the desired outcomes.”

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Tags

- Offshore and marine