Text: Thomas Masuch; Photos: PFW — 06 September 2020

While the rest of the aviation industry is counting on Additive Manufacturing to deliver better designs (and ultimately lighter jets), industry supplier PFW Aerospace GmbH is following an entirely different strategy at its headquarters in Speyer, Germany. The company, which manufactures components for the likes of Airbus and Boeing, is using industrial 3D Printing to reduce its material requirements and thereby lower its production costs. It sounds quite simple, but this approach could change the competitive landscape in aviation in the years ahead.

Dr. Markus Gutensohn, head of production technology at PFW, has been dealing with Additive Manufacturing in his department for seven years. He started by researching powder bed technologies, which led to a discovery that was initially sobering, but eventually proved that much more valuable to the company. »PFW doesn’t produce any parts that would benefit economically from the use of SLM technology,« Gutensohn reveals.

The aviation supplier, which was founded 107 years ago and now employs more than 2,200 people, counts pipe systems among its key business areas. »There’s no point in optimizing the topology of pipes, for example; in terms of bionics, they already have the perfect shape,« Gutensohn explains. Instead of writing off 3D Printing entirely, however, he and his team of engineers realigned their strategy and began looking for different AM technology.

Tobias Theel is one of the engineers who mainly works on Additive Manufacturing at PFW. The 27-year-old figured out that the best match for the company was »technologies with higher build rates, like powder deposition welding «. Rather than using design programs to optimize components, PFW »takes a look at existing parts to find out where the use of AM would be more cost-effective,« as Theel puts it.

"Some of our requests are incorporated straight into the development of the next generation of machines."

The company now sees the most potential in areas where parts are machined from solid blocks of titanium. Here, conventional milling techniques have two challenges to contend with: First, titanium is obviously hard and difficult to mill, which results in lengthy machine operations and a high degree of tool wear. Second, aircraft-grade titanium is quite expensive at around 50 euros per kilogram. Milling machines often end up turning 90 percent of these metal blocks into swarf, which indicates a great deal of optimization potential. According to Theel, directed energy disposition (DED) can help reduce the »buy-to-fly« ratio – that’s weight of the raw material needed to build a given component to the weight of the component itself – from 9:1 at present to just 2:1.

A Partnership along the Rhine

To achieve this aim, PFW became one of the first companies in its industry to enter into a partnership with BeAM. This young manufacturer of systems for powder deposition welding – a variant of the DED process – is based just around 120 kilometers up the Rhine in Strasbourg, France. »That means it doesn’t take long for a technician to get here if we’re dealing with some kind of issue,« Gutensohn points out. His department develops and fine-tunes many of PFW’s production technologies, including in connection with automation, pipe bending systems, and workstations that have been adapted for Industry 4.0. Of the 16 engineers who work there, four focus solely on Additive Manufacturing.

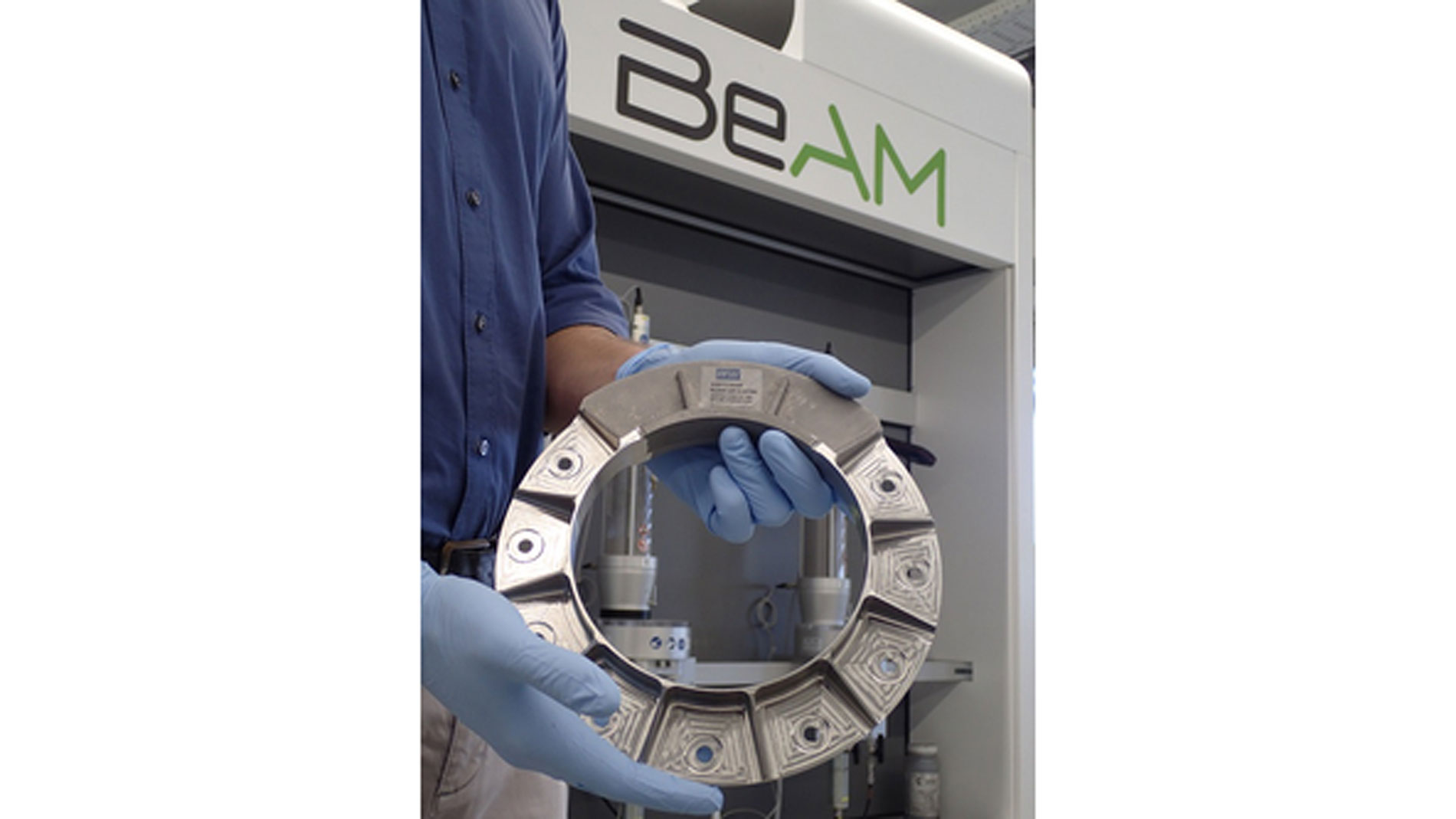

Since acquiring a Modulo 400 from BeAM in mid-2018, PFW has produced numerous components and prototypes for tensile tests and also conducted other types of trials. The two companies are working together closely to »get the machine ready for industrial series production«. To improve their ability to define their requirements, PFW’s engineers have also developed and built their own AM unit for wire deposition welding. The machine and its three-kilowatt laser are capable of 3D-printing components and test pieces in inert atmosphere, which Gutensohn says makes it possible to establish a benchmark between powder- and wire-based laser deposition welding.

The production director describes PFW as a company on the cutting edge of industrial laser deposition welding, which enables it to provide BeAM with valuable references. These include specifications that are meant to further industrialize BeAM’s systems, such as by reducing setup and downtime or optimizing maintenance and process monitoring. Here, Gutensohn also appreciates the young French company’s flexibility. »Some of our requests are incorporated straight into the development of the next generation of machines,« he says. »With a bigger manufacturer, we definitely wouldn’t have that much influence.«

Frédéric Le Moullec, business development director bei BeAM, affirms that »working with our customers and taking their feedback into account is the focus of our development strategy «. He goes on to explain that DED technology has long been used to repair parts in the aviation sector, but is now evolving into an industrial method of producing high-quality components. »Our partnership with PFW has given us the chance to build up a great deal of technical expertise in this area and continue to support the industrialization of their production, « Le Moullec adds. »By sharing ideas with one another, we’ve been able to optimize our inert atmosphere and develop process parameters that make it possible to achieve material characteristics in line with the aviation industry’s requirements.«

Sights set on automated Production

To avoid becoming overly dependent on one manufacturer, Gutensohn reports that PFW is planning to install two other AM systems from other providers at its development facilities in Speyer in the months ahead. Meanwhile, we get a glimpse of the more distant future one floor down in the same building. There, robots are fitting dozens of milling centers with components, and the entire process chain has been automated to the greatest extent possible.

In their efforts to advance DED technology as fast as they can, PFW’s engineers are trying to make a very complicated process »as simple as possible«. For example, they are only using one type of powder (from the GE subsidiary AP&C), which is already being used for electron beam welding after receiving corresponding certification from Airbus. In addition to individual components like retainers or star flanges, an array of substrate plates can be found near PFW’s development unit from BeAM. These are used in the company’s own labs to develop parameters for things like creating grinding patterns or carrying out tensile tests. Here, Gutensohn and Theel want to come up with statistical evidence that DED can be relied on to deliver consistent quality over extended periods of time.

While Additive Manufacturing is just one piece of the puzzle in this process chain, it’s surely the most sophisticated one. From 3D Printing to heat treatment, blasting, milling, X-ray inspection, and crack testing, there are more than 15 steps involved – »and the cleaning processes bring that number up to 25,« as Theel points out. His boss sees this as a crucial advantage for the company. »We have a lot of experience in all the other production processes, and we’ve had them certified for the aviation sector, as well,« Gutensohn says. »Plus, we’re quite good at working with titanium and know how it will react in each processing step.«

An integral Part of PFW's Technology Road Map

This much is clear: Only those with in-depth knowledge of the entire process chain can make industrial use of Additive Manufacturing. Gutensohn wants PFW to reach this milestone by 2023, but admits that the company »may have to get there even faster«. His department will develop the technology up to TRL 6 before handing it over to production. So far, PFW has reached TRL 4 with its DED process.

The fact that the Speyer-based aviation supplier might need to speed up its implementation is due in part to the tremendous amount of potential this new production method presents. »On an industrial scale, the component costs are sometimes even lower than the current material costs, where machining is involved,« Gutensohn reports.

While he says that this applies to fewer than 100 components in PFW’s current products, Gutensohn believes an aircraft could eventually house several thousand such parts. This is where the use of AM could prove to be a real factor in competition; companies that don’t get on board will be at risk of losing market share. It’s no wonder that Hutchinson – the global manufacturer that acquired an ownership stake in PFW in early 2020 – has made metal deposition welding an integral part of the company’s technology road map.

AM TECHNOLOGY:

Additive Manufacturing for metals - DED Technology

A structured overview of the complex and multi-layered world of Additive Manufacturing processes, process steps and fields of application can be found in our AM Field Guide.

PFW Aerospace GmbH

The foundation of Speyer’s aircraft production operations, which can be seen from the city’s famous Romanesque cathedral, dates back to the year 1913. Over the years, some of which included manufacturing automobiles, the company known as Pfalz-Flugzeugwerke (»Palatinate Aircraft Works«) evolved into an international supplier of tier-1 and -2 aviation components that generated around €450 million in turnover last year. PFW now produces some 1.24 million parts each year – landing flaps, reserve tanks, structural components, and more to complement its renowned pipe systems. Along with its base of operations in Speyer, the company has plants in England and Turkey. Twice in PFW’s history, it has been majority-owned by Airbus. When the company was to be sold in 1996, ownership was instead transferred to its employees; Airbus then reacquired a majority stake in 2011 before eventually selling its shares to the Hutchinson group in 2020. Although PFW retains close ties to its former owner, it now has a total of 50 customers, including Boeing.

Tags

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aviation and aerospace