Text: Thomas Masuch, 19 February 2024

Having identified the technology as an excellent counterpart to traditional forms of art, the Hamburg-based artist duo Sutosuto is using 3D printing in more and more of their projects. A selection of their works was on display in the AM Art Space at Formnext 2023.

Just inside the entrance, Captain Hamburg, the Rolling Stones, and German rock legend Udo Lindenberg stand ready to greet visitors. A bear that has made itself comfortable on an oversized currywurst awaits at the next corner, right next to a blue whale swimming through a tangle of straws and cocktail glasses. The studio of Sutosuto is home to a surreal world of characters both real and dreamed up, each of which has been put to canvas with a potent combination of creativity and skill.

Image: Mesago / Mathias Kutt

The first time you wander down its main hallway, however, there’s little indication that the place boasts more 3D-printing expertise than some industrial users of AM. It’s not until you make your way through the maze of various workshops (which cover everything from painting to woodworking and grinding) that it gradually becomes clear: 3D printing has not only well and truly arrived in this artistic haven in northwest Hamburg – it now plays an important role in Sutosuto’s creative process.

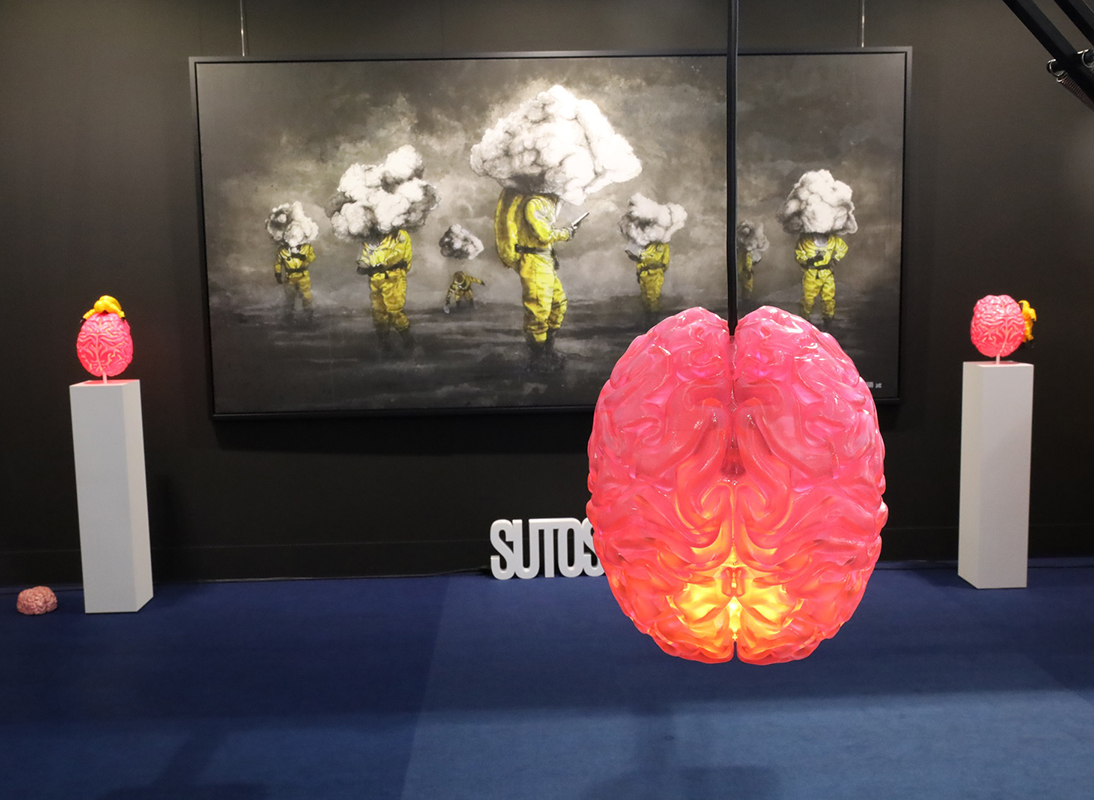

Letting it brain on the trade fair floor

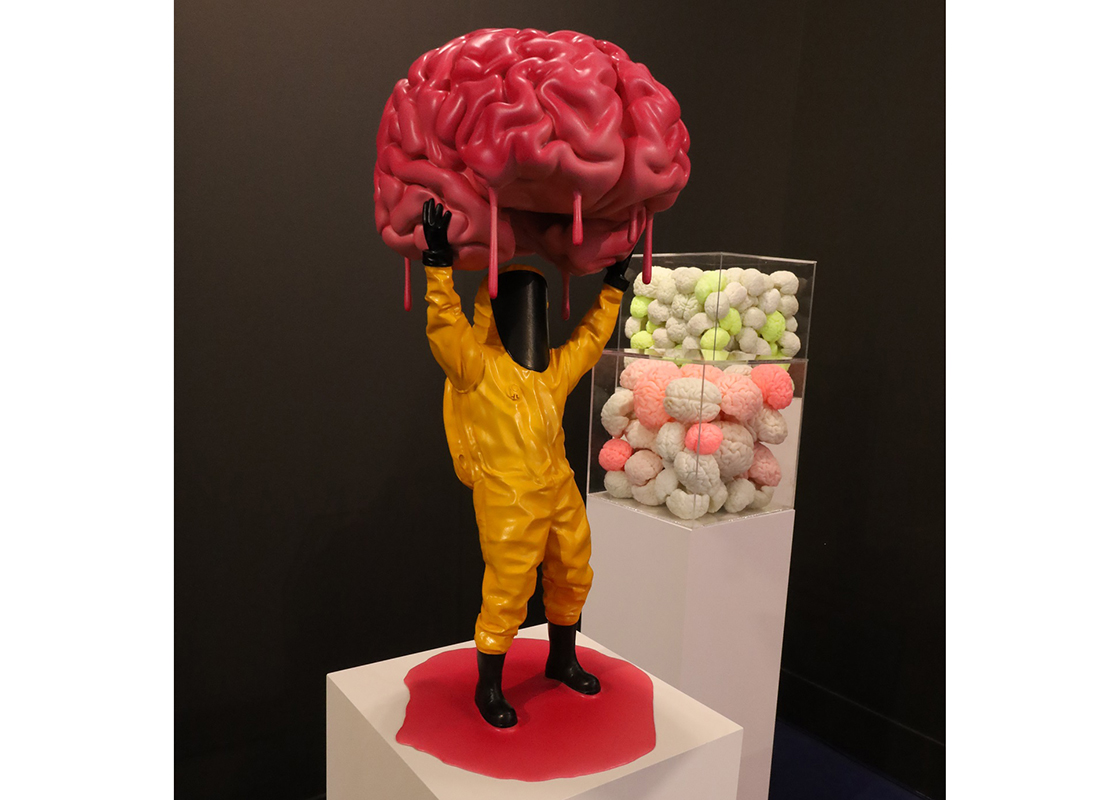

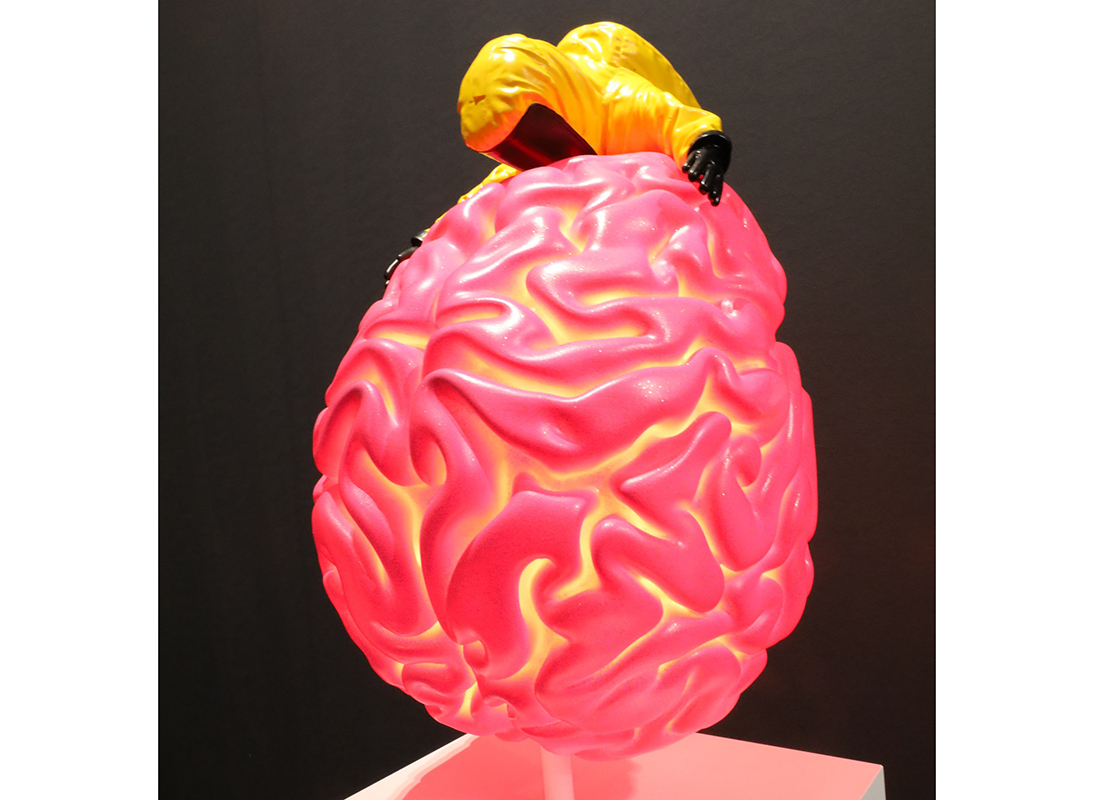

In cooperation with Formnext 2023, the artistic duo consisting of Susanne Dallmayr and Thomas Koch presented a series of works in the AM Art Space, a special showcase that drew attendees in droves over the course of this year’s event. At the heart of the 63-square-meter showcase was a current Sutosuto exhibit dubbed “Let It Brain”, which comprises a great many 3D-printed brains that light up in myriad colors. The space also included the self-consuming monster Hazfat and numerous large-scale paintings, one of which features faceless people in protective gear who are meandering through a sparse landscape with their heads in digital clouds. “The response to our booth was overwhelming. The best indicator was a comment we heard more than once: ‘Your booth was the best! Keep it up!’” Dallmayr reports.

Over the more than 20 years in which they have been making art together, she and Koch have developed a striking artistic style rooted in painting and graffiti that now also includes large-scale sculptures – and 3D printing. In other words, the two of them are not “just” designers, painters, and illustrators, but digital artists and sculptors, as well.

Let it brain: The Formnext 2023 Art Space der Formnext 2023. Images: Thomas Masuch

Dallmayr (now 37) and Koch (38) have known each other and been in a relationship since they were both students at htk Hamburg. After that, they started their careers in different fields – she as an illustrator, and he at an advertising agency.

Still, both carved out time for making art outside of work, which they initially devoted mainly to painting, drawing, and graffiti. The success they had led to Koch’s decision to focus entirely on his craft, and Dallmayr followed suit some time later. “Our network has grown constantly, and we’ve continued to evolve artistically, as well,” Dallmayr reveals. “That’s what enabled us to take part in exhibitions right from the beginning without any major promotional effort, and we also found people to buy our art.” Meanwhile, the two were even able to create images four to five meters wide – for the cruise ship MS Europa 2, for example, or the bar of the Hamburg hotel 25hours. “That’s basically the dream of any creative person who’s focused on art,” Dallmayr points out.

First forays into 3D printing

In 2015, it was a wall that needed decorating in that Hamburg bar that gave rise to the idea for a particularly affecting work of art: a peace sign made of intertwined hands, which was exhibited at Formnext 2022. At first, however, it was impossible to turn the concept into reality. “Our initial thought was to use plaster casts, but the weight and complexity involved in the project quickly made us realize that wasn’t going to work,” Dallmayr recalls. “We didn’t have any alternatives, so we filed the idea away for the time being.”

After finding themselves unable to get the peace sign out of their heads, she and Koch revisited it the very next year and contemplated other ways to make it happen. Both artists had been using 3D software for designs and models for some time, which made 3D printing a relatively obvious possibility. They thus created an initial rough mockup in three dimensions and sent inquiries to a wide range of service providers. The responses Dallmayr and Koch received were not all that encouraging. “People either told us that the overall project was unprintable, or impossible to calculate – or they quoted us a price over 250,000 euros, which was obviously a little outside of our budget,” Dallmayr explains.

Images: Sutosuto

The long road to Peace

With the artwork that would eventually be named simply Peace once again proving seemingly impossible to realize, Sutosuto opted to create a monster instead. The duo’s attempts to find a partner for creating their peace sign led to a cooperation with FKM Sintertechnik, a company based in Hesse. This in turn resulted in Hazfat, a self-consuming ogre of overconsumption standing 1.4 meters tall and weighing in at 210 kilograms, which was cast in bronze using a 3D-printed mold. “We found the technology stunning and knew right away that we had to keep working with it,” Dallmayr says. “It wasn’t long before we’d assembled our own 3D printing lab.”

After plying their trade on canvas during the day, the duo spent their evenings and nights researching printer technology, software, dimensions, materials, and more. The Sutosuto studio now features a 3D-printing workshop with a large-scale FFF printer, multiple stereolithographic printers, and even an upcycling loop, which consists of a shredder and filament maker that the duo says can turn household waste into fresh printing material. All these creative efforts don’t leave Dallmayr and Koch much time away from their creative space or computer screens, of course. “After the past four years, I’d quite like to go on vacation for more than two days again,” Dallmayr admits. “We’re creators, though – even when we do get a little room to breathe, we just end up starting another new project!”

While the duo was exploring the possibilities of 3D printing, they also made progress on Peace. Their first attempts at printing in their new workshop quickly made it clear that this creation would be best kept in-house. After spending another two and a half years on digital design, sculpting, and writing algorithms, Sutosuto succeeded in printing around 200 high-resolution hands in 2021.

Let it brain was the motto at the Formnext Art Space.

Sutosuto combined motifs from her paintings with 3D-printed brains.

A real coincidence: Markus Schmidt (right) studies mechatronics in Bad Homburg and brought a 3D print of his own brain to Formnext. Even the two artists were amazed.

Images: Thomas Masuch

This resulted in more than a hundred individual parts that were then glued together to form an impressive overall work measuring two meters to a side. The duo finished the surfaces of the hands to make it look as though they had been cast from plaster. At Formnext, even some 3D printer manufacturers were fairly stunned by the result. “Lots of people asked us whether it was really 3D-printed; they couldn’t believe that such refined, detailed surfaces were possible with an object of this size,” says Koch, recalling the 2022 event.

From artists to AM experts

Pulling this off required nothing less than pioneering work in applying 3D printing to the world of art. Dallmayr and Koch spent day after day reworking pieces, grinding surfaces, and reading up on things like machines and their technical idiosyncrasies, printer maintenance, component size, and the use of support structures. Their expertise in 3D printing has grown so extensive that Koch has even been offered jobs as a technician or design engineer while attending Formnext.

It’s a fair question, actually: Is this still art, or more akin to engineering? “The technical aspect is also art – the art of engineering,” Koch insists. In the long term, the two artists want to explore even closer connections between 3D printing and their other artistic production techniques. Their ideas thus far have included a combination of painting and 3D-printed sculpture.

“Great competition for old forms of art”

These days, around half of Sutosuto’s works come from 3D printers. Dallmayr and Koch mainly use additive techniques in their free artistic efforts. These are projects that don’t pertain to any particular commission – Hazfat or Peace, for example – and enable Sutosuto to realize their philosophies without outside influence or the constraints of a specific concept. That said, “free” doesn’t come for free; the duo has to pay for the production costs themselves in these cases, which can run into the five figures. “This is important to how we see ourselves, but it’s also an investment in our future as artists,” Koch points out. The self-image he and Dallmayr share contains aspects of sustainability, democratic renewal, and the battle of the good in humanity against dictators, oppression, digital oversaturation, and environmental pollution.

Meanwhile, the role 3D-printed sculptures are playing in their commissioned work continues to grow. “For us, additive manufacturing is a chance to bypass conventional forms of production that are really energy-intensive – copper or bronze casting, for instance – and deliver a level of quality that doesn’t look like it’s 3D-printed at first glance,” Koch explains, with Dallmayr adding: “3D printing is great competition for old forms of art.”

Both are convinced that the work they have put in thus far has given them a technical edge in the art market. “Hardly anybody else is capable of realizing projects at this level,” says Dallmayr, who goes on to point out that 3D printing is about much more than concepts and digital files. “The deciding factor is always the operator,” agrees Koch, who can now appreciate the challenges he and his partner faced in creating Peace and Hazfat. “We overcame pretty much every obstacle you can encounter in connection with 3D printing. Anything we run into now probably won’t shock us anymore!”

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Tags

- Additive Manufacturing

- Design and product development