Text: Thomas Masuch, 21 May 2024

The collection of products decorating our meeting room reflects the rich variety of Antonius Köster’s creations. A car’s gear stick amicably shares the space with a designer lamp, numerous prostheses mingle with an erotic toy, and slate-look porcelain plates offer a cool counterpoint to a leopard-print mug. Most of these works were 3D-printed, and for some, the product development process was driven by Köster himself. For almost every one of them, the man can tell a story about combining modern technology with traditional artisanry in a creative way.

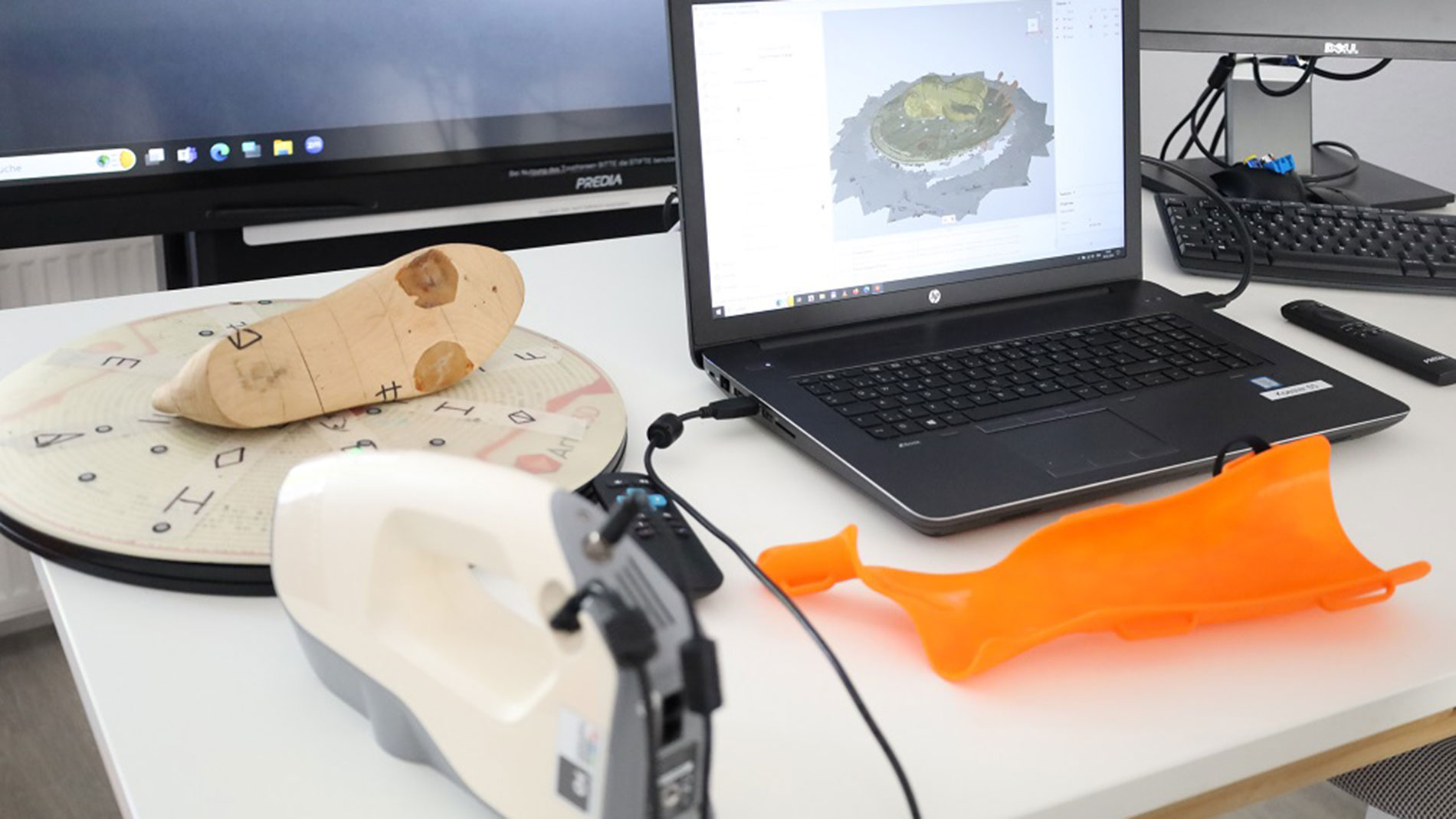

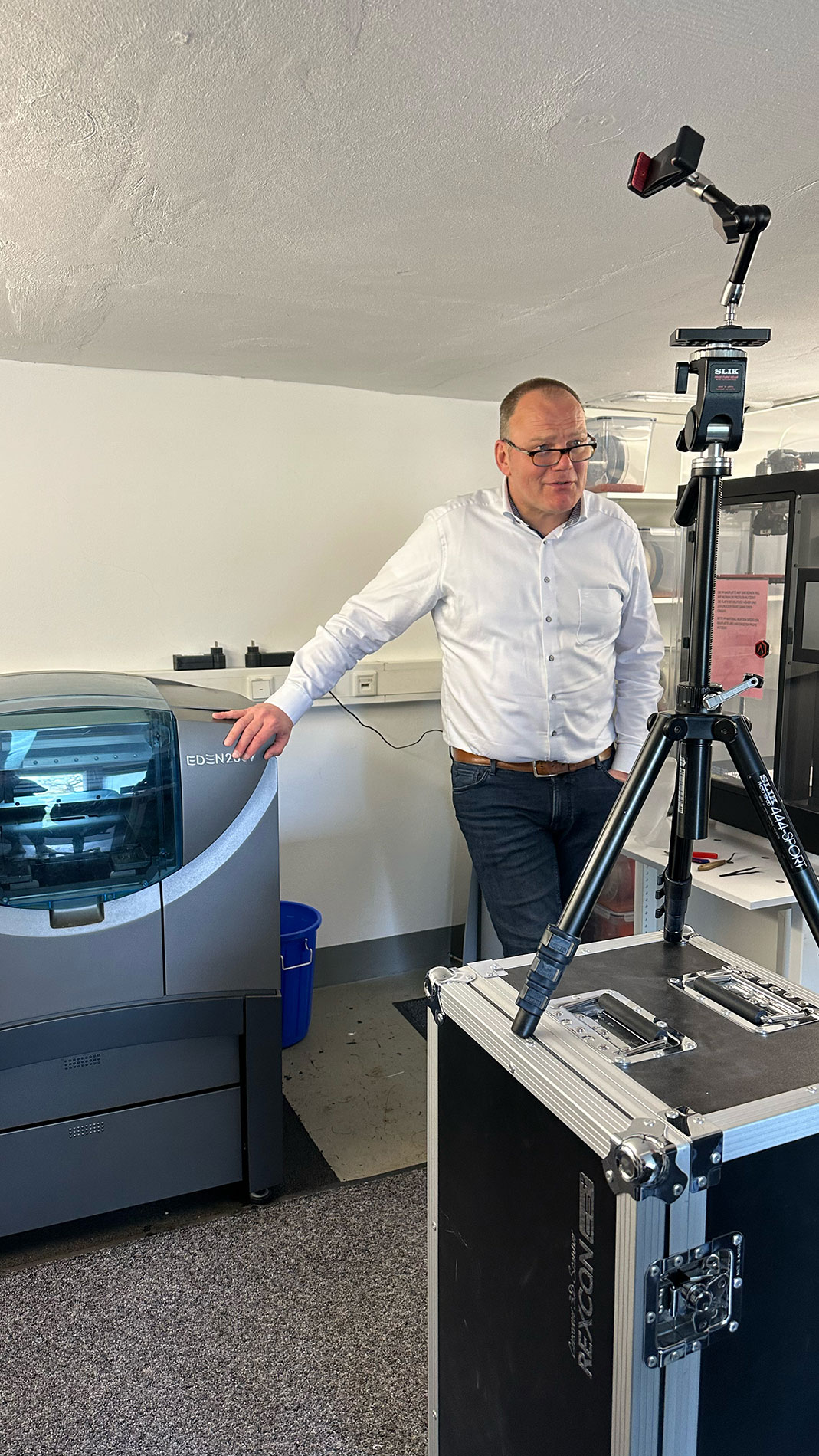

The 59-year-old Köster, a model builder by training, specializes in working with design data. That’s why the beating heart of Antonius Köster GmbH & Co. KG isn’t its workshop (which houses four FDM 3D printers), but a room one floor up that features around a dozen top-quality scanners and sees use as a space for training courses. A bold mission statement adorns one of the walls: “We can make any shape production-ready” – “...but the data is essential,” Köster adds with a smile.

The leopard-print mug was something Köster 3D-printed over a decade ago for a TV commercial in which the German comedian Hape Kerkeling extolled the virtues of Krüger-brand coffee. One of his much more recent accomplishments involved producing release samples for a new series of porcelain creations from Villeroy & Boch. In the space of just one week, Köster provided the company with 3D-printed samples that eventually evolved into a highly successful collection. The plates, cups, and saucers in it are still shaped by the design data he created. “That’s our concept of creativity – taking new ideas and making them ready for production,” Köster explains. One particular aspect of his company’s creative expertise relates to mapping decorative surfaces in the digital realm, often with an eye toward 3D-printing them in the real world. In some instances, Köster’s innovations have even resulted in patents, as he explains with a wry smile. “Unfortunately, there’s no mention of us in those patents even though a lot of our know-how has gone into the corresponding products. That’s just how it goes for service providers like us.”

A first responder of sorts

“We’ve carved out a niche as a first responder of sorts,” says Köster, who favors medical metaphors and technical jargon (we’ll explain why later). “In other words, we’re the ones companies call when they’re in some kind of fix.” Along with creative support, the emergency services the firm provides include 3D printing.

Köster – a native of Sauerland (western Germany) – got his business off the ground 30 years ago in the city of Meschede, where his first “office” also happened to be his kitchen. Today, the company has 10 employees and is headquartered on Köster family property. In one of its offices, which is only separated from the building’s private residential portion by a single wall, Christian Alexander sits at a computer working on some design engineering for a customer. He was Köster’s first employee and has now been with the company for 27 years. With his down-to-earth manner, Alexander’s boss seems to have little in common with start-ups from the United States, whose investors dream of rapid scalability.

The importance of data

Köster has actually been exploring 3D printing since all the way back in 1991. His company’s workshop still has an Objet Polyjet printer from 2009, which Köster claims still works as well as plenty of new printers. That said, he also relies on new technologies when doing so makes sense. The man is bursting with practical ideas, but doesn’t jump on every hype train and takes a critical view of some developments in the industry.

Köster has seen a great many companies struggle to introduce and utilize such innovations. “Some of them buy a 3D printer after being taken in by the manufacturer’s sales representatives, only to realize that they don’t have any corresponding data,” he explains. He goes on to cite the development of the aforementioned porcelain collection as an example. “3D printing helps us offer demo products, but the data involved eventually serves as a basis for an entire production setup. The data is where real value is created.”

Focus area: orthopedics

Data also plays an integral role in the second mainstay of Köster’s business – the one that’s even more critical to its balance sheet. Since 2003, Antonius Köster GmbH & Co. KG has been a sales partner of 3D Systems and Oqton (for their Touch hardware and Freeform software, respectively). The company serves the German-speaking and Benelux countries and select customers in other regions, which amounts to around 600 active clients in total. Of that number, 80 percent operate in the field of orthopedics or other areas of medicine, where 3D printing is used for purposes like planning operations.

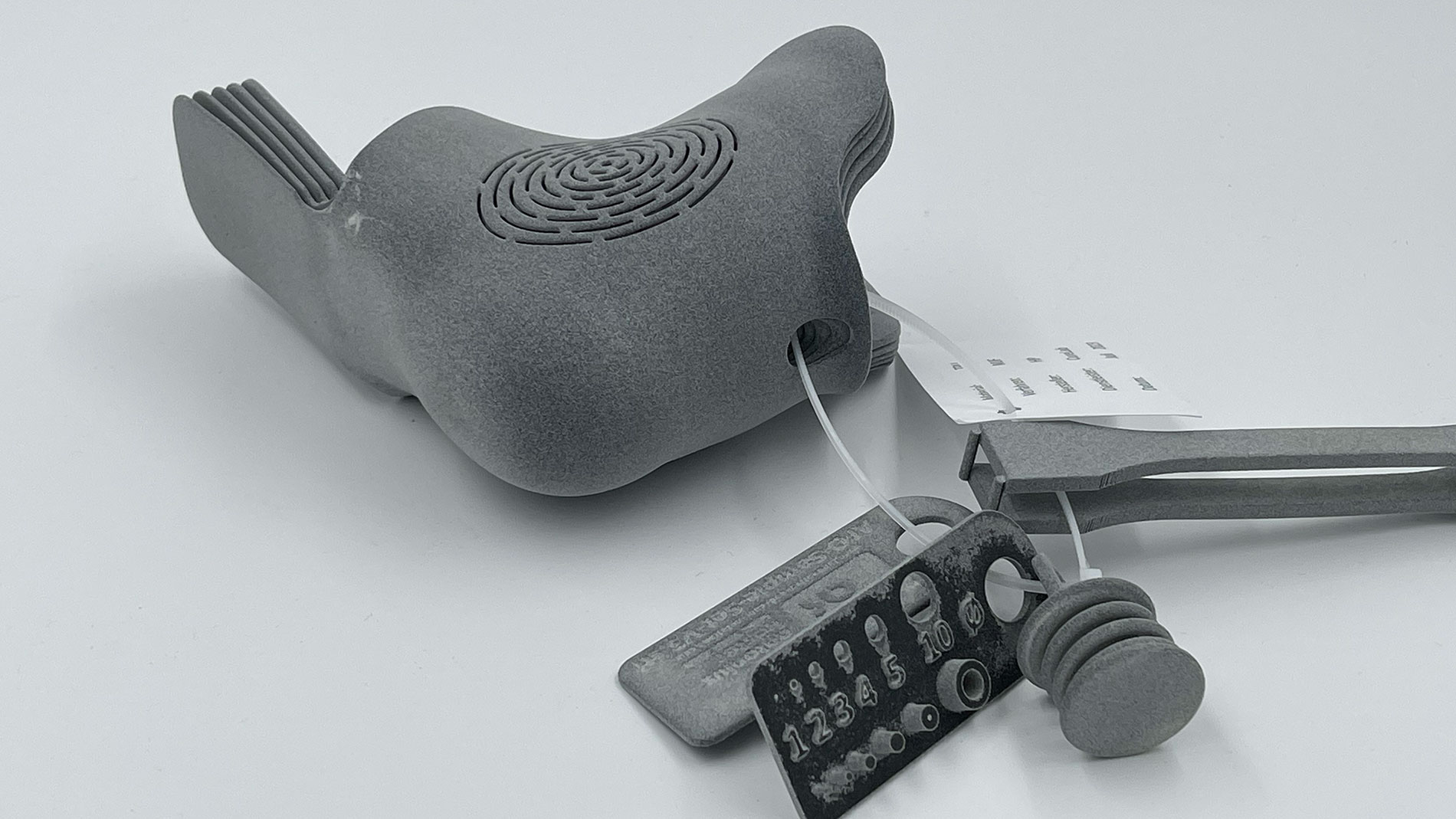

According to Köster himself, Freeform is particularly well suited to organic shapes. A haptic pen makes it quite easy to “take hold” of digital models and make modifications. “In this respect, we’re a lot faster than parametric software solutions,” he explains. There are numerous potential applications, particularly in orthopedics. As Köster points out, you can’t just scan a foot and print an orthosis; there needs to be space around the toes, or else someone is going to feel the pinch when walking. “That’s the difference between a form that fits and one that actually works. It’s something we’ve learned from orthopedic technicians.” To that end, digital scans need to be adjusted accordingly. In doing so, Köster does his best to incorporate the technicians’ more traditional knowledge and marry it to digitalization.

Training is key

“At the end of the day, it’s about enabling a craft business to work with new technologies,” Köster offers in summary. In a highly traditional industry like this, he says this often takes a lot of convincing, especially when tried-and-true business processes are to change. “The best approach is to work with young people that haven’t gotten so used to the conventional way of doing things.”

Another prerequisite is having orthopedic technicians that are able to acquire the necessary expertise, which is why training is another essential component of the work done by Köster and his team. He can explain, for example, how to optimize the scanning process, the best way to combine TPU and PA 12 in a prosthesis, or how thick a sole needs to be based on the patient’s weight and the length of the limb in question. This results in products that “have a real impact on people’s lives,” an enthusiastic Köster says, recalling a four-year-old boy who was able to walk for the first time thanks to a 3D-printed prosthesis. “Things like that impress me more than a 3D-printed rocket engine!”

A past life spent in hotel rooms

Before the pandemic, Köster was on the road visiting customers around half the time; he racked up around 180 hotel stays every year, and one of his employees added as many as 120. These days, the company’s training program is largely online. “It works really well this way, too,” Köster affirms. And of course, not traveling as much anymore means being able to spend more time with his family and explore the forests around Meschede on his bike.

Meanwhile, doing things digitally has led to advancements in Köster’s training courses, as well. Instead of being arranged in hefty blocks, they now comprise shorter units that can be completed over a longer period of time. “Customers can also send in products for us to scan and process on the computer,” Köster adds. The training program takes longer now on the whole – two or three weeks in some cases. “It enables employees to start working productively much more quickly, though,” Köster points out.

Orthopedics companies and clinics

The company’s clients also include quite a few clinics in places like Münster, Basel, and Salzburg. In some of these locations, there are AM centers with large numbers of printers that produce haptic models for surgical preparation, which shorten the duration of such procedures and can help surgeons achieve better results. Custom medical devices are also developed, such as 3D-printed ventilation masks for preterm babies. A tiny pacifier of this kind with built-in tubes was made at the Charité hospital in Berlin, where it has also been put to successful use. This is an area where Köster believes 3D printing is just getting started. “Development is proceeding slowly,” he says. “It would help if things that have turned out well were collected in some kind of official way as evidence of the benefits of new technologies.”

In contrast, additive manufacturing is already much more widely established in orthopedic technology. Köster’s most important customer segment comprises both small trade businesses and large orthopedics companies with hundreds of employees. “Two-thirds of our clients use 3D printing,” the company’s owner and CEO estimates. He says that although additive manufacturing will always be a complementary technology in this field, “the scope of the 3D-printed products used by orthopedists and dental technicians is huge.” According to Köster, some of his company’s customers print three to four thousand orthoses each year. “It’s a level of potential a lot of people just aren’t aware of,” he adds. At the same time, Köster laments the lack of specialized personnel that would enable him to increase his sales considerably. “We’d be generating more revenue if we could deliver operators along with our products!”

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Tags

- Medical technology

- Digitization

- Tool and die making

- Services

- Design and product development