by Thomas Masuch — 8 February 2021

The cement industry is one of the world’s largest emitters of CO2. 3D Printing is therefore associated with the hope of building in a more material-friendly and sustainable way. Meanwhile, even greater sustainable potential lies in alternative building materials: MIT researcher Sandy Curth and collaborators from the University of California, Berkeley have bravely taken on one such substance that dates back millennia – clay – and have already 3D-printed some initial test buildings on the plains of Colorado. The challenges, however, are immense.

The local farmers certainly did their share of smirking at the unfamiliar construction technology required. Indeed, simply operating it took as many people as an entire construction site of the same size. But they also offered some well-intentioned advice: "You guys need to mix in more straw," one said. "How are you going to insulate it or put a roof on it?" asked another. Sandy Curth – who worked with a team consisting of researchers Logman Arja, Ronald Rael, and Virginia San Fratello that 3D-printed the first clay prototype on the prairie near Antonito, Colorado – was pleased with how people with lots of hands-on experience reacted. After all, they were dealing with this new technology and didn’t see anything superfluous – much less threatening – in it. "That’s an indicator that the technology is going in the right direction. People are starting to see these machines as something that’s robust," Curth reports.

"Sustainability is about minimal use of material."

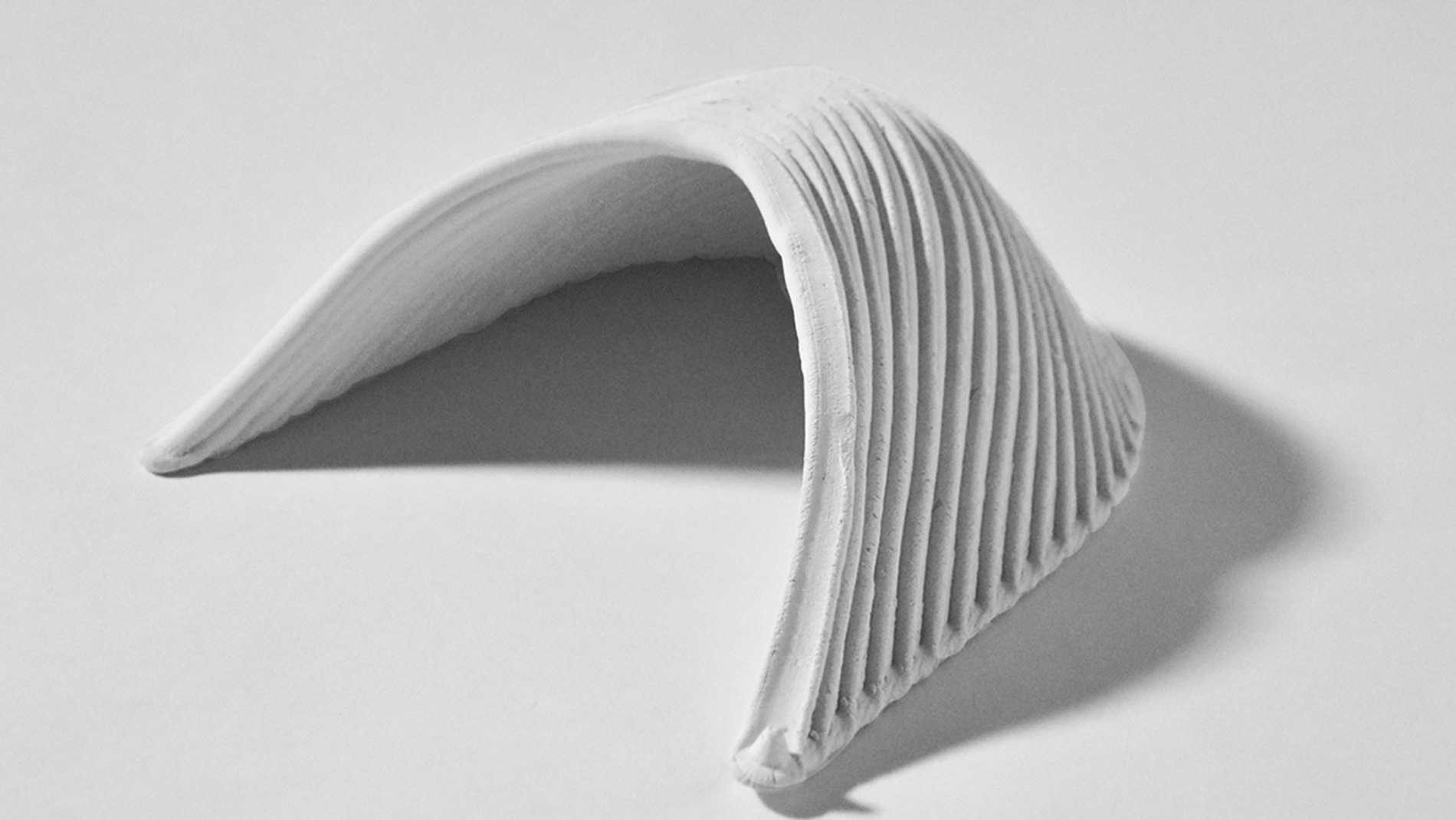

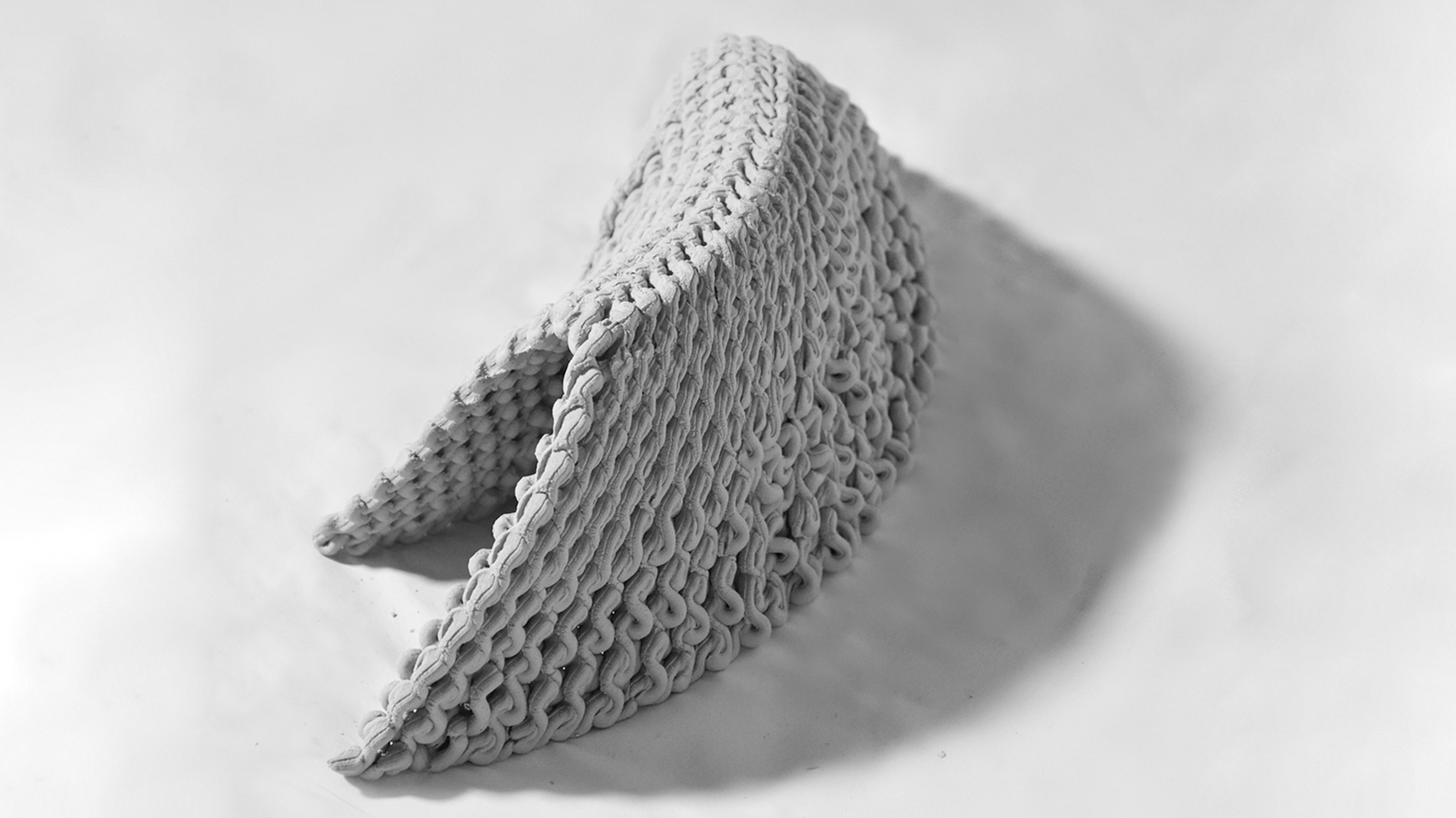

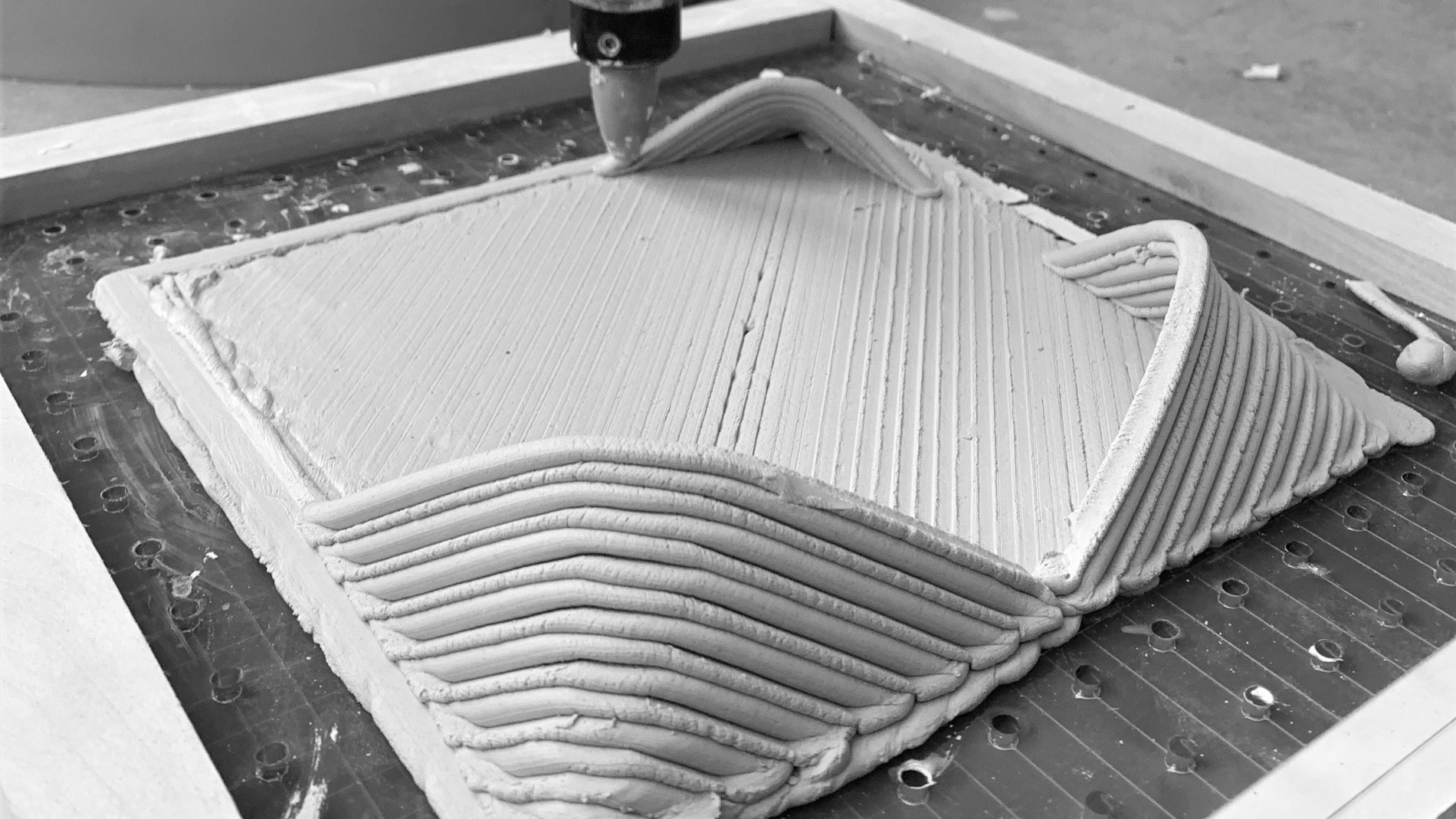

The technology used by the MIT/UC Berkeley research team has deliberately been kept as simple as possible. The building material (a mixture of local sand, clay, straw, and water) is pumped through a tube and placed in the desired location by the arm of a SCARA-type robot. In this way, one coil of clay overlays the next, forming the honeycomb walls of a round structure that looks like a mixture of a beehive and an indigenous lodge. Curth, who cites sustainability as his main motivation, uses resources as sparingly as possible in terms of both materials and technology. "Sustainability is about minimal use of material and being able to use minimal amounts of equipment on-site to produce something that is large and complex and highly functional," he explains.

Examples of the capabilities of clay in architecture can be seen on the Arabian Peninsula in Wadi Hadhramaut, which is also known as the "Chicago of the Desert" thanks to its nine-story buildings. Or look to Weilburg / Germany, where a six-story adobe house has withstood countless long, cold, and damp winters since 1836. In recent years, the growing quest for sustainability has given new momentum to the use of adobe in the construction industry in Europe, the United States, and China. For instance, clay was used extensively in the new headquarters opened by the organic food company Alnatura in 2019. Walls made of rammed earth are clearly in vogue – especially where they don’t play a load-bearing role. The advantages of this building material, which has been used for thousands of years, are enormous compared to cement: Besides being free of harmful substances and climate-neutral in production, it provides a healthier indoor climate and makes a striking visual impression thanks to its natural structure. Sandy Curth even sees a "super growing industry" in the U.S..

NOT A LABORATORY

That said, working with 3D Printing does pose major hurdles in this context. Unlike in the industrial 3D Printing of metal, where the process takes place in an environment that is as clinically constant as possible, many variables can hardly be predicted when 3D-printing clay. This starts with the material itself, which should be available locally to avoid long transport routes. Among the other regional characteristics in play, environmental factors such as sunlight and wind play a major role; the clay has to dry before it can support further layers, after all. "And actually, we 3D-print in an environment that’s not unlike a real construction site, where you’re outside, the weather changes, and equipment gets roughed up and pushed around. It’s not a laboratory," Curth points out.

Another unusual factor is time. While there is concrete that hardens very quickly, 3D-printing earthen material requires patience. "Concrete has a fixed curing time. For us, you have to consider drying," Curth reveals. This meant it was only possible to print for two to three hours at a time; then the waiting began. In the meantime, however, the MIT researchers were able to move their clay 3D printer to the next building and continue there. "We were printing in three or four places at once and started to have a continuous workflow across the construction site," the MIT researcher says.

Leveraging this technique in a professional setting (which would also include certification, of course) seems almost impossible at first glance due to the many unpredictable factors at hand, but Sandy Curth remains confident. In order to get a handle on the numerous variables, he is developing software that calculates appropriate 3D printing parameters based on things like the current weather conditions and the properties of the specific material in use. In the future, Curth plans to make it compatible with both earthen and concrete structures to give 3D Printing an additional boost in his chosen field. "Improving the software is going to make this technology available for widespread use in the construction industry," he predicts.

To that end, Curth is working with various concrete manufacturers – even if that does somewhat cloud the sustainability aspect. "We can validate a lot of what we want to do with earth, and any material savings allowed by 3D Printing can significantly lower the embodied carbon of a concrete building," he maintains. In addition, Curth has his sights set on much more unusual applications in developing his 3D printing technique for clay. "I think earthen construction with 3D printers as a kind of construction model is maybe the most compelling model currently running on Earth for how we’re going to build buildings in space."

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Tags

- Construction and architecture