Text: Thomas Masuch, 3 September 2024

At University Hospital Münster, 3D printing is supporting both patient care and research.

Before you start applying 3D printing to the field of medicine, you should definitely know the rules inside and out – which is something Dr. Martin Schulze has been spending a lot of time on in recent years. The engineer and orthopedist heads the 3D-Center at University Hospital Münster (UKM). With the help of a team that includes printing experts, radiologists, microbiologists, and other engineers, Dr. Schulze not only oversees the 3D printing of incision templates and models for preoperative planning; he also deals with the frameworks that are meant to ensure UKM’s compliance with the relevant regulations.

For an example of how complicated that can be in a sector as highly regulated as medicine, look no further than the relatively simple process of 3D-printing an anatomical model. Here, it makes a big difference whether the model will “only” be used for demonstration or to explain a procedure to a patient, or for planning an upcoming operation. It might even need to be a sterile object that will be used for tactile navigation purposes in the operating theater.

The 3D-Center at UKM claims to be the first clinic in the world to have had its printing process certified in line with the stringent requirements of the ISO/ASTM 52920 standard. This in turn opens the door to the overarching ISO/ASTM 13485 standard, which enables hospitals to manufacture and administer medical products directly at the point of care. “That sets us apart from other clinics of our kind,” Dr. Schulze explains. “One of the things that made this possible was the fact that the 3D-Center was planned based on a new concept and is now part of a network that includes all of UKM’s other departments.” He views the center’s certification and the way in which its quality management efforts have been organized as the foundation of all its research. “If I want to find out what kind of benefits can be achieved with 3D printing as an on-site resource, the main thing I need to ensure is safety,” Dr. Schulze points out.

In Münster, medical products classified in risk categories 1 and 2 are currently manufactured and used; they include things like organ models for preoperative planning and templates for surgical incisions. Moving up to risk category 3 – implants – is one of Dr. Schulze’s definite plans for the future.

A variety of 3D printing technologies

The project to establish the 3D-Center was largely financed by the EU’s REACT program. “Without in-house funds from our orthopedic clinic, the medical faculty, and UKM itself, however, pulling off an undertaking of this size would have been impossible,” Dr. Schulze adds.

The 3D-Center officially started operating on 2 February 2024. That said, the preparations had already begun back in 2022, and the summer of 2023 witnessed the delivery of the facility’s beating heart: an SLS printer weighing in at 1.4 tons. Today, the 3D-Center has more than seven different plastic 3D printers at its disposal, which also support technologies like FDM, SLA, and DLP. The environment in which these machines operate meets all the requirements of manufacturing medical products – for instance, a constant ambient temperature of 21 degrees (C), specially refined compressed air, and a nitrogen generator that produces the shielding gas necessary for SLS printing. The different printing technologies and individual process steps are also kept physically separate to prevent contamination. These safety precautions are so strict that of all the 11,500 employees at UKM, just a handful have access to its 3D printers.

Requests on the rise

As a partner to the various departments at UKM, the 3D-Center is far more than just an AM service provider. “We don’t just 3D-print based on data; we handle the entire process needed to solve a given problem,” Dr. Schulze affirms. In the months since the center opened, demand for its expertise has grown constantly within UKM. Each week brings five to 10 new requests from a wide range of departments. Not all of them turn into a project, though. “We always have to start by assessing whether we can meet the need in question in a way that makes sense,” Dr. Schulze explains, adding that the corresponding imaging has to be of a sufficient quality.

As for potential use cases for 3D printing in medicine, he sees plenty – including in radiation therapy, where patient-specific skin protection can reduce the side-effects of such treatment. “There are all kinds of application areas you can consider, but you can’t get started on all of them at once!”

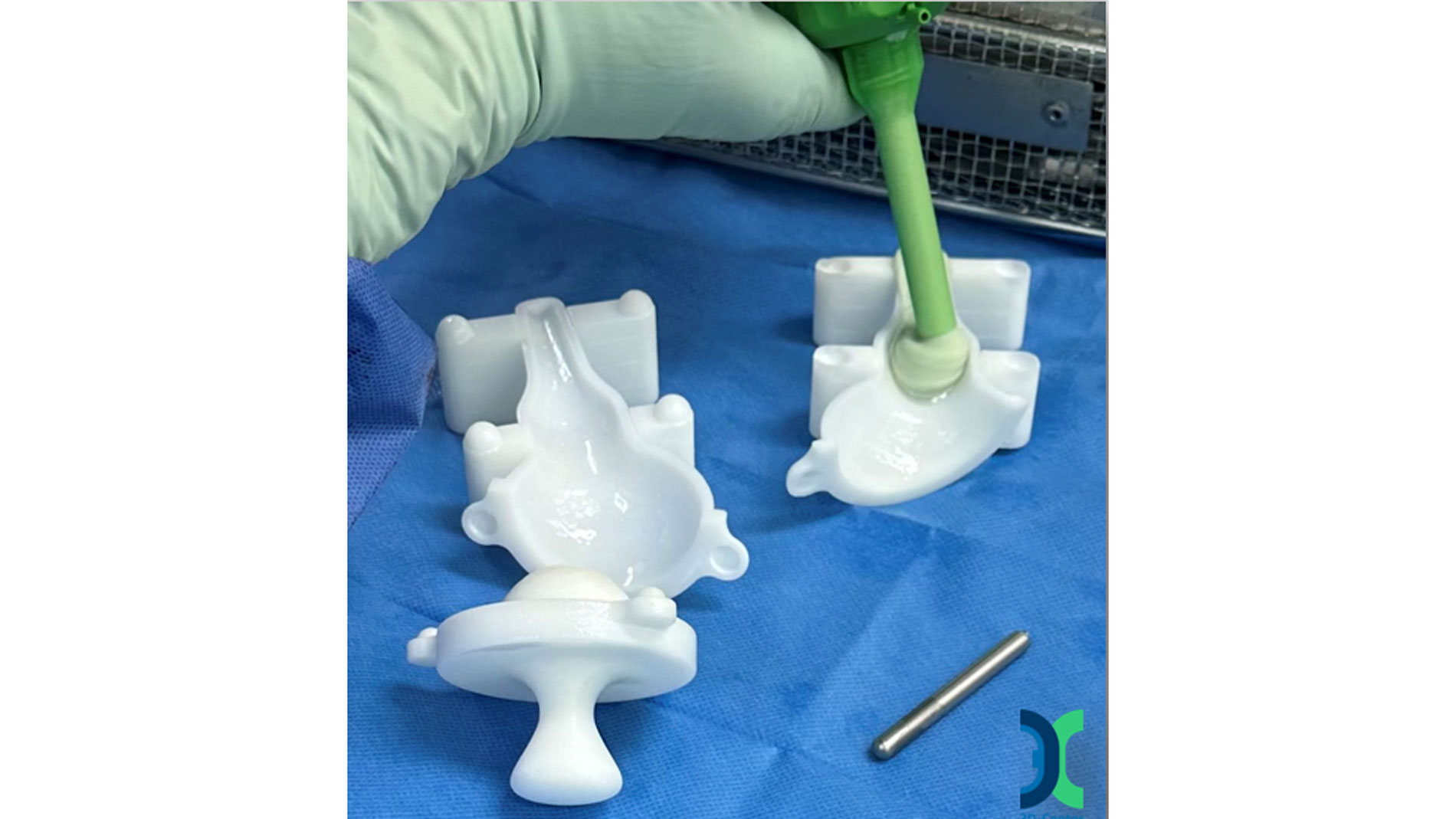

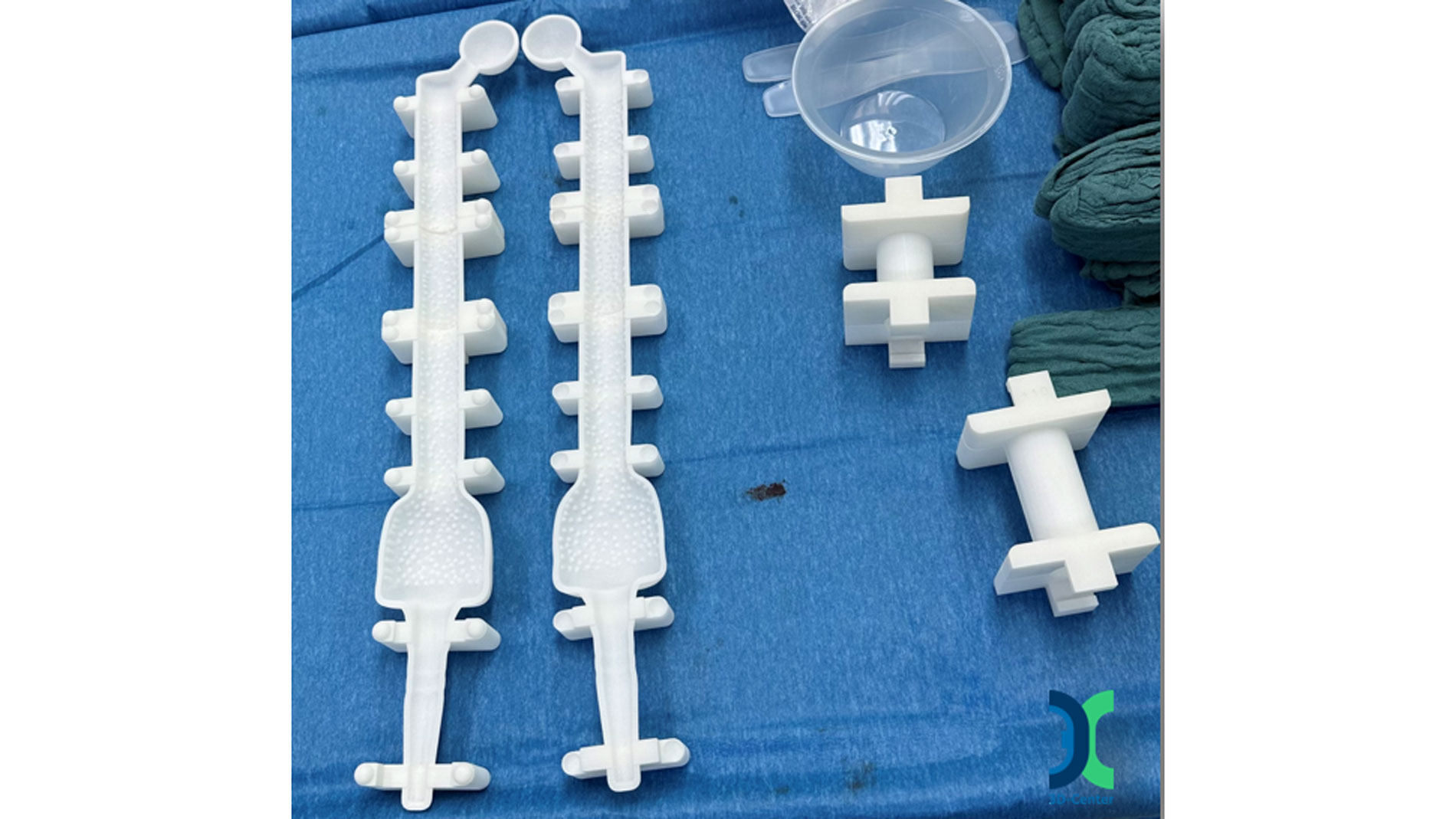

Creating a spacer with a 3D-printed mold

Dr. Schulze performs operations himself on a weekly basis, relying on 3D printing for complex procedures. A case he handled just a few weeks ago shows how helpful the technology can be. Severe inflammation had developed around a prosthesis a patient had received to replace her entire femur, along with the knee and hip joints. That meant the implant had to come out. “Treating inflammation like that is a complex and lengthy process. You have to wait until it has healed before inserting a new prosthesis,” Schulze explains. This is why a device called a “spacer” is typically inserted for the time being. “Until now, the standard procedure involved the surgeon creating a spacer by hand using bone cement,” Schulze continues. “That extends the duration of the operation, however, and the results aren’t always good enough – especially with spacers as large as the ones needed for femurs.” He thus opted to have a mold consisting of several components printed at the 3D-Center prior to the operation. During the procedure, the mold was filled with bone cement, which dried quickly and enabled prompt insertion.

Different from medtech companies

Its focus on research, development, and excellence in medicine makes the 3D-Center quite different from most companies in medical technology. “Our 3D printers aren’t used nearly as much, of course; production efficiency isn’t the priority here. We’re about research, development, and providing the best possible care to each individual patient,” Dr. Schulze points out.

During the operation, the mold was filled with bone cement, which hardened quickly for rapid insertion. Image: UKM

The 3D-Center’s director goes on to describe 3D printing as more of a subsidized endeavor for UKM. Hospitals in Germany receive flat compensation for each operation they perform, but special cases like the one involving a 3D-printed spacer aren’t covered in health insurers’ billing catalogs. That said, 3D-printed solutions are typically only used in highly complex and difficult situations at UKM – meaning for operations most clinics would need to subsidize anyway.

“Lives have been saved”

“From a moral perspective, we can’t always question how profitable a given procedure is,” Dr. Schulze says. “After all, we’re often entering uncharted medical territory in our 3D printing.” In Münster, patients have received treatment after having been classified as inoperable by other clinics. “When you get right down to it, lives have been saved,” declares Dr. Schulze, who recalls one particular case involving heart surgery on a child. “It was initially a question of whether operating was even possible. Eventually, we were able to reevaluate and plan the procedure thanks to a 3D-printed model.”

That’s not the only reason why Schulze believes that this technology will take on a much greater role at clinics in the future. “As experienced doctors retire, we’re facing a shortage of medical expertise,” he says. 3D printing could thus help maintain a high standard of care, and it can bring its benefits to bear in smaller clinics, as well. “When the cost of an operation is estimated at €60 per minute and a single operating model can already help reduce the duration of the surgery by an hour, it’s definitely worth it,” Schulze explains, adding that less time spent under anesthesia also reduces the risk of complications

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Tags

- Medical technology

- Research and development